“There’s only one other person wearing a mask here… and they’re carrying a pillow.”

On an evening in July, I ventured back to the old country of Santa Clarita, CA, a place I last graced to get shot with the Covid-19 vaccine under the shadow of Colossus— both the name of the Six Flags rollercoaster and my unbridled enthusiasm to take one hopeful leap from death’s light. Now it’s 3 years later and the disease is far from gone, though my sharp eye at people-watching-slash-quietly judging has long since slowed. After a while, you choose to accept other people’s unbothered approach to their own mortality— though I do make an exception when said people look like they’re about to publicly nap.

“Do you know if the pillow was theirs?”

I’ve been married to my husband for 6 years and now every second was cast in a new light. “Why else would they be carrying it??” He was not accustomed to how strange this sight was to the natural couplings of small theatre-going: the patrons double-fisting self-printed programs with grocery store bouquets; Kirkland water bottles with computer-printed “telegrams”; an exasperated sigh right as I exited my Chevy, close enough to my stranger’s ear to require explanation: “Sorry, it’s… our second time out here this week.” A mother was pulling the arms of her two Middle School-aged children past me in the parking lot, now cathartically laughing because that’s the body’s response when you accidentally expose the true state of your human condition. Fortunately for her, I was too distracted contemplating how a community college performing arts center in Canyon Country would be transformed into a Jewish shtetl.

What keeps theatre companies performing Fiddler on the Roof? “Tradition!”1 This play is as ubiquitous to theatre calendars as The Nutcracker is to ballet troupes, with the character list alone being a conflict-averse director’s dream (got a grade’s-worth of children and a few eager parents? Have I got a township for you). Though the same could be applied to another theatrical stalwart Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (got a grade’s worth of pubescent boys and one unlucky girl? Have I got some brothers for you!). It’s not a fork in the wood young theater people consciously take, but one rather chosen for us by the higher powers of our respective drama temples— which is a long way of saying this is my first ever trip into Anatevka.

I have no excuses. I grew up in a neighborhood nicknamed “Little Jerusalem”. My Mother loves to tell a story where I, the perfect 9-year old hostess, invited my Hasidic neighbor friends over for a playdate, only to ruin their religiously-sanctioned fast by offering pop tarts. Fiddler was just not a chapter in the theatrical canon I opened to read— or perhaps, somewhat unconsciously, I assumed it wasn’t “my story” to understand and at the very most re-tell. It’s not like the razzle-dazzle Bible story by Andrew Lloyd Webber felt any more natural, but at least this was a god I knew (that being the God of Sequined Vests) versus the god I didn’t know (that being the God of Having a Dad in the House). Fortunately for me, it’s third time’s the charm for our evening’s director.

“It had always been my philosophy that the purpose of theatre is twofold— to entertain and to educate. Fiddler is a perfect illustration of a piece that does both very well.” It was the year 1995 and the news of the Oklahoma City bombing was still tragically dissolving through the media cycle. Somewhere north of LA County, TimBen Boydston was directing his first production. “Tomorrow in America, it could be any of us.” TimBen writes, feeling the weight of the world when all he wanted to do was lead fictional people in song. 11 years later, he would direct bottle dancers while battles raged in Darfur, Iraq, and Lebanon. Now on this night in 2023, the threats are both far-away and in our own backyard. “There is a proverb that says, ‘there is nothing new under the sun.’ It seems that in our supposed ‘age of enlightenment’ here in America, we need this story today as much as we ever have.”

It makes sense that a director would wanna mount the same work several times, seeing fresh images in its kaleidoscope with the clarity of new light— after all, it takes two-and-a-half viewings of any Coen Bros movie to truly understand if it’s supposed to be funny. When Fiddler debuted on Broadway, it was an almost-immediate hit. The film came just 7 short years later.2 The licensing for touring companies was released without hesitation. When a work imprints itself so quickly and steeply into the culture, it’s natural for its etymology to be eventually lost— which was exhibited accidentally by the woman seated behind me muttering, “Oh, like the Gwen Stefani song,” when tonight’s Tevye sang, “If I Were a Rich Man”. But that’s really skipping ahead and we still need to set the table for supper.

It’s opening night, so TimBen and his co-director Laurie take to the stage in evening wear. I learn quickly that this is the company’s once a year “big show”. Yes, this state-of-the-arts facility— like too many homes in 2023, is a rental. Typically, CTG lights up their 277-seat stage in nearby Newhall, which is where my friend Jake thought he was sending me when he strong-armed me to go. “Sorry in advance,” he texted— which I took less as an indictment and more as a theater person’s involuntary prayer. “Lemme know how it goes.” It’s hard to invite outsiders to an intimate temple. Harder still to encourage them to see something as omnipresent as this show. Even though I’ve somehow escaped it like a cat weaving between obstacles, I learned through the 2019 documentary Fiddler: Miracle of Miracles that a production of Fiddler is performed every day in some place throughout the world— forcing me to imagine some complicated bookie’s office in an undisclosed location, “Santa Clarita just bumped South Asia— put it on the map!” Or perhaps theaters just get their jury summons, with a pre-fab’d stamp of Harvey Fierstein’s signature.

I’m worried for this start. The house is not quite full. The balcony barely open to the public. The audience mostly moseying to their seats as TimBen and Laurie have been on-stage vamping for 10 whole minutes, and somewhere, a covid-conscious woman luxuriates in her ability to reserve an empty chair with a home-brought cushion for the prophet Elijah. But then, the opening chords of the signature song plays. And our curtain parts. And our stage is bare, save for a three-walled shack. And then there’s Andy Mattick as Tevye, standing next to the titular character. And it doesn’t matter what comes next, because I’m already crying.

Some musical notes just render you helpless. Like a glorious soprano in “Ave Maria” or Spinal Tap’s“Lick My Love Pump” in D-minor (“the saddest of keys”). Call it musical manipulation, or call it a masterpiece— all I know is that it’s working and I mentally mark one point for the play I never thought I’d see. As for Mattick as our lead, he’s as lively and spirited as you’d expect for a guy who happens to be best friends with God— which makes an awful lot of sense, given that by day Andy’s a co-pastor at the Valencia United Methodist Church.

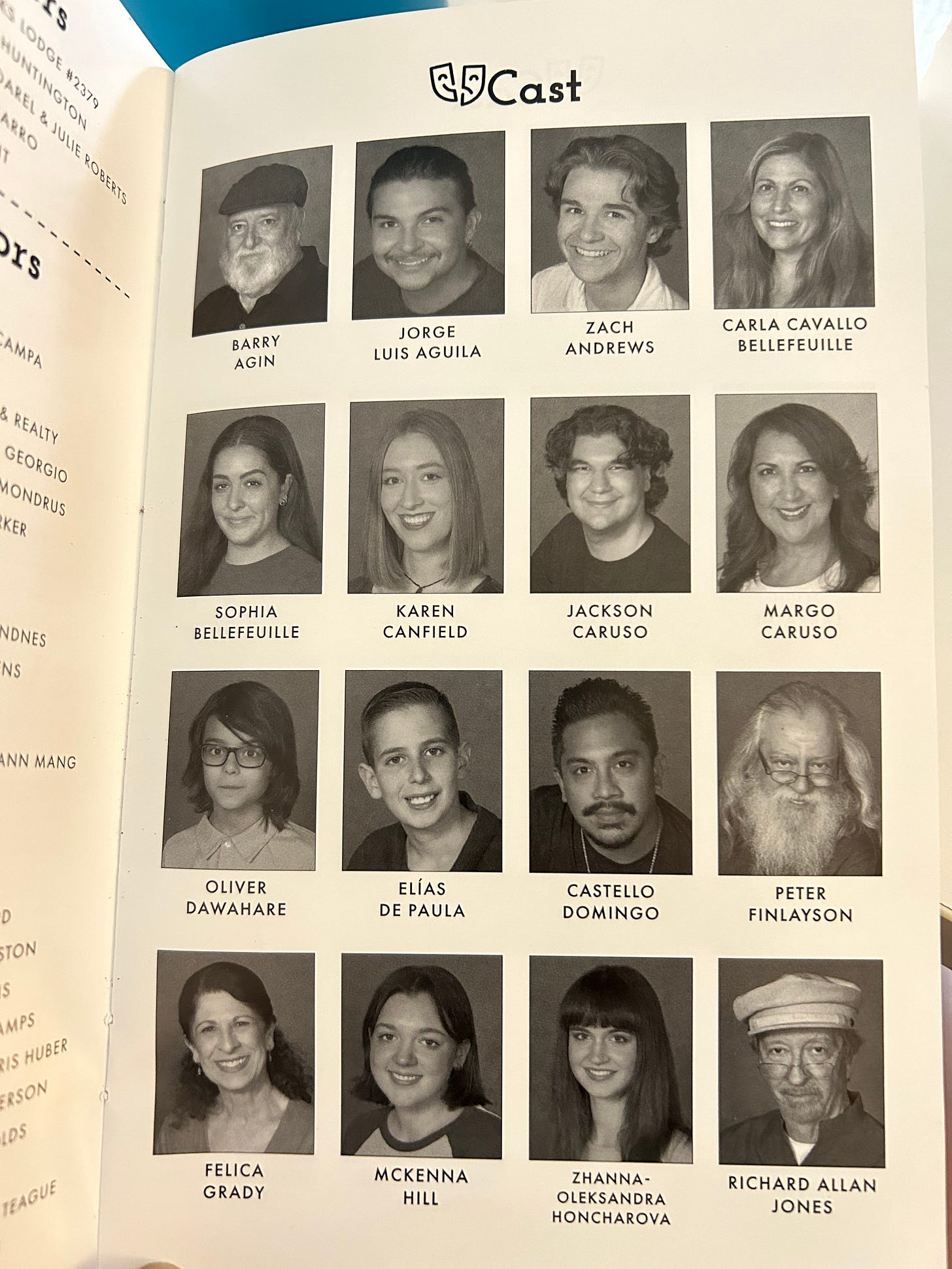

Let’s hear it for the Goys. They’re all over this damn production. Let’s hear it for the Hispanics, they’re dancing in this circle, too. There’s Jorge Luis Aguila as Motel, clearly a newcomer, but crafting his performance as Tzeitel’s lover with the reverence and care you’d desire in a future son-in-law. Then there’s Jackson Caruso as Perchik, having a blast even though it’s apparent he was lassoed into this life by Margo Caruso, who multi-tasks playing Shaindel on-stage and co-costuming backstage. Castello Domingo plays a line-less member of the ensemble, but his recent theater resume is long (Spot Conlon in Newsies! Vladimir in Waiting for Godot!) and his ambitions expand beyond the stage, in a Graphic Design degree at Arizona State. Performing is just for the summers, as most love affairs are often relegated to.

But what of our main family? They’re strong and sturdy, just like their Papa. All 5 actresses playing Tevye’s daughters lean and love on each other through the cocktail of nerves and sweat that so naturally forms when your youngest cast is new to the stage (and also using their bios to give themselves co-billing as “actress”, “dancer”, and “lover of dolls”— Skye Violet as Shprintze, thank you for unlocking a triple-threat I didn’t know I needed!!). Mattick as Tevye continues to ground us, but even he knows the stage belongs to the villagers.

Back in the early 1960s, when Fiddler was just a glimmer in book writer Joseph Stein’s eye (or perhaps more accurately, a headache shared with lyricist Sheldon Harnick), Stein made a point to name every single character, even if they barely glimpsed behind a beer mug. His intention was verisimilitude. His aim was to ensure every citizen felt like they mattered. His quote read, “this is a musical about seeing the entirety of a place that you fled,” rather than it being flattened to a footnote. Following that intended realness, Jerome Robbins would choreograph without precision (except of course, for the aforementioned bottle dance). This was a show about real people really celebrating, real wedding parties getting rowdy, and real pains of persecution.

Following that outline, it’s impossible to hold a production of Fiddler — however amateur — to the same standards of its musical peers. To ridicule it for being unpolished or off-key is like handing out grades for a child singing their “ABC’s”. That isn’t to say that tonight’s performance requires that disclaimer— there’s plenty to love in Donna Marie Sergi’s energetic performance as Yente (truly the original messy bitch of our modern times). Or Carla Cavallok Bellefeuille as Tevye’s wife Golde, a role that can easily fold on-stage resentments into a justifiable character choice, but instead she’s all enthusiasm and joy and motherly care. I’d be remiss in not mentioning Josh Larralde as Mendel, the Rabbi’s son, whose incredibly tall stature makes any line that interprets the Bible feel like it’s commanded from God himself just by proximity alone (they’re also sharing the stage with not one, but TWO family members. Congratulations Larraldes, you just secured your honorary trophy at this year’s CTG Awards!).

What I mean to say is — specifically to my friend Jake who requested an update — is that the goodness of this production is almost moot to the play overall. Movies love making movies about the movies, but boy does theatre love making theatre about the theatre. And after witnessing this classic, I simply can’t imagine a show that better exemplifies the cozy claustrophobia of belonging to a performing company more. There’s that specific experience of both loving and crabbing at your cast mates; opening yourself to new members, but balancing light skepticism that your Utopia will somehow be betrayed; fearing for the future, so you clutch tightly to the tradition of re-mounting the same shows partly out of comfort, partly to provide answers.

In the aforementioned Fiddler doc, the late great Joel Grey gets a letter: “Do Americans like this show? Because it’s so Japanese.” Grey was on the verge of directing the first all-Yiddish production which would go on to break all sorts of records and continues Off-Broadway to this day. In the moment, he laughed it off with amusement, but behind the note was a discovery: these international productions were not just dutifully excising the canon for the glory of Broadway to hopefully rub off on them in the wash, they were seeing themselves. They were seeing their towns. They were seeing their sisters or Fathers or wives and yes, their own persecutors. Sure, West Side Story debuted in the same year with similar themes, but we know what we see when we think of New York, and we know what we project when we conjure the murky image of our own personalized “old country”. Going into this show, I braced for the potentially ill-advised premise of a mostly non-Jewish Fiddler, but that was not even close to being part of the point.

I was wrong to think Fiddler wasn’t “my story,” much in the way non-theater people think there’s only “one type of musical” (and why is it always Cats). And though I’m not itching to renew my vows, if only to incorporate “L’Chaim” into my reception repertoire3, I get it now. I appreciate it. My crying began at the start, but continued on during the “Sabbath Prayer,” because holy singing has its way of permeating beyond any denomination. I fell in love with the on-stage village, despite their range of talents and diversity of flaws. I even grew to appreciate our mismatched audience, whose chatter didn’t stop at “Rich Man,” and whose mystery of the pillow will continue to haunt me like the pear dream or a horse helping you go to college.

I’m curious what’ll happen in another 5 years. Or 10. Or 20. When TimBen dusts off his directing binder to explore the life of Tevye once more. I’m curious what future tragedies will make the text that much more relevant. Worry how close the plot will fall to our homes. Wonder how much Universal Studios charges for renting their WaterWorld stage, hopeful that depiction will be more apocalypse-fantasy than apocalypse-now.

Canyon Theatre Guild’s production of Fiddler on the Roof closed on August 13th, but their production of Arsenic and Old Lace takes its final bow this weekend. Sign up for tickets here.

Their next show Ken Ludwig’s The Gods of Comedy begins on September 22nd and runs through October 29th. More info here.

Join me next week, where I venture to Costa Mesa to witness the first of two RENT productions that — somehow impossibly — has a bunch of hot people who are nearly 10 years younger than me.

A Dad joke that doubles as a plea that the AMPTP needs to end this WGA strike right fucking now.

For context, the Wicked movie is currently being shot— almost 20 years to the day of when the Broadway show first defied gravity.

Which of course LIN MANUEL MIRANDA DID.